A few weeks after the “Czajka” service, there was another lifeboat call where I had to transfer from the lifeboat “Foresters Centenary” to a vessel needing assistance. In this case, she was unmanned as her crew had been rescued a few hours previously. The vessel was the motor barge “Gold”.

|

| Barge “Gold” just completed at Berwick Shipyard |

|

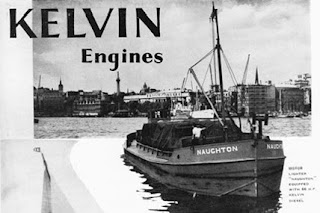

| Kelvin Engine Advert highlighting Barge “Naughton” |

|

| Jimmy Gold (L) & Charlie Naughton (R) |

|

| Preserved Kelvin K4 Engine |

The first two barges were named after the music hall (vaudeville) double act of Glaswegian comedians Charlie Naughton and Jimmy Gold. Their speciality was slapstick using buckets of whitewash and soapy water .

For over half of their professional careers of 47 years and 11 thousand performances Naughton and Gold were teamed up with two other double acts to form the “Crazy Gang”, on stage and radio. The most famous double act in the “Crazy Gang” was Bud Flanagan and Chesney Allen with their familiar song “Underneath the Arches”.

The barges “Naughton”, “Gold” and “Silver” transported general cargoes such as 200 tons of grain, and tinned foods in and out of the Thames usually as far north as Great Yarmouth and south to Dover. A retired skipper of the “Naughton” and “Gold barges wrote in 2009 that “Their handling at sea was poor” and that “they went where they wanted to go when loaded, not where you wanted!”

The rescue of the crew and the subsequent salvage of the barge “Gold” were logged as two separate events, as described here.

Rescue of the Crew of the Barge “Gold” 8th December 1954

The barge ”Gold” was sailing home to Rochester from Hull with a cargo of castor meal (fertiliser) on 8th December. She had been at sea since the previous day but had been partly driven back by heavy gales. Her engine failed at about 5pm and for an hour the crew of 2 tried to restart it. However by 6.20pm, the “Gold” was only one mile off shore, about 2 miles west of Sheringham. On hearing that more gales were forecast the barge’s crew fired red distress rockets which were seen by the ship “Rota” which broadcast a distress call.

Maroons were fired at 6.25pm and the Sheringham Lifeboat “Foresters Centenary” was prepared for launching by 6.45pm. At the angle on the slipway the lifeboat engine would not start and she had to be returned to the level turntable. On the second attempt to launch the lifeboat ran off the side of the slipway, jumping partly out of the carriage runway and jammed. The tractor was then used to push the carriage in an attempt to float the lifeboat off but the tractor took in water from a large sea and lost power. A very large wave lifted the lifeboat off the carriage and with the aid of the haul-off warp she got to sea.

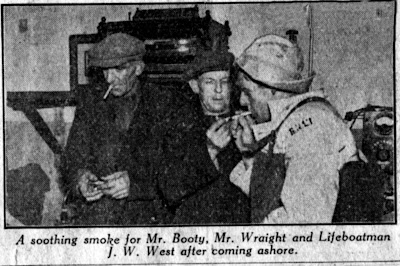

By this time the “Rota” had taken off the crew of the “Gold” and they were transferred to the “Foresters Centenary”. They were found to be exhausted and so were brought ashore and taken to the Burlington Hotel for the night.

|

| My brother Jack getting a light from one of the rescued crew of the “Gold” |

Salvage of the Barge “Gold” 9th December 1954

Coxswain Henry “Downtide” West considered that the unmanned barge “Gold” was in danger of blowing ashore, especially as the weather forecast was poor. He asked permission of the Honorary Secretary of the Sheringham Lifeboat, to use the lifeboat to standby and possibly recover the barge to Wells, the nearest safe harbour. The Hon. Sec. agreed.

The Royal National Lifeboat Institution (RNLI) allowed their lifeboats to be used for Property Salvage under Section VI of their Regulations. However, the owners of the barge contested the salvage claim made by the lifeboatmen and as a key witness in the subsequent litigation, Henry prepared a statement. The contents of this statement describes the events of that night and is presented here.

Service to the Barge “Gold”

I have been a fisherman at Sheringham for the last 16 years, saving four years when I served in the Royal Navy during the last war.

I am second coxswain of the Royal National Lifeboat Institution motor lifeboat “Foresters Centenary” stationed at Sheringham, and I launched with her at about midnight on Wednesday 8th December 1954. Two extra men were in the crew making a total of 11, as we intended going to the barge “Gold”, the crew of which were on shore.

When we got alongside the “Gold” I jumped on board her with three others of the lifeboat crew. The “Gold” was dangerously close to a rocky ledge, the ebb stream was running to the westward and the “Gold” was heading into the tide and wind, which was blowing a SE gale.

The “Gold” was riding to one anchor and was pitching and on occasion rolling. She was deep in the water and seas were breaking over her.

When I got on board, I at once took steps to establish connection with the “Foresters Centenary”. She gave us a 3 inch rope which we made fast forward on the “Gold”, passing it through her port hawsepipe . We then obtained one of the “Gold’s” ropes and passing this through her staboard hawsepipe, we gave it to the “Foresters Centenary” and both ropes were secured over the lifeboat’s quarters.

The “Foresters Centenary” went ahead on her engine and took the strain of the “Gold” whilst we weighed her anchor by means of a hand winch forward. My coxswain had instructed me to be particularly careful to inform him immediately the anchor was off the bottom, because the barge was so close inshore that he wanted to get her weight and prevent any windage.

The “Gold’s” anchor was on a very long scope of chain and it took us a considerable time to heave it in. Immediately I found it was coming off the bottom, I hailed Coxswain West and he at once put the “Foresters Centenary” head to seaward and held the barge whilst we got the anchor up. He then went ahead and the “Gold” was towed out to the northward for about one mile, when a course was set for Wells. We did not stow the anchor but left it ready hanging from the hawse.

I took the wheel of the “Gold” and steered her. She had a diesel engine right aft and one mast forward but I saw no canvas. I knew her engine had broken down. Her hatches were battened down and she was laden with a cargo of castor meal. The wheelhouse of the “Gold” was on the foreside of the engine.

She was not easy to steer, because the spokes of the wheel came within a few inches of a steel shelf on which the binnacle was housed. When a swell caught here and threw her off course, it was difficult to get her back again without one’s hand being caught in between the spokes of the wheel and the shelf. She sheered about quite a lot, with the wind and sea astern of her.

When we had proceeded about 2 mile towards Wells, there was a violent squall and both tow-ropes parted. We immediately hove in the broken parts and the “Foresters Centenary”, after going round us on three occasions managed to get a line to us on which we bent one of the barge’s wires which we had got ready and which was then hove on board the lifeboat and secured, and towing recommenced.

At about 2 a.m. we arrived at Blakeney and conditions then became very bad, with wind and sea increasing. The “Gold” rolled heavily and took a large quantity of water over her, so that it was impossible at times to get forward to tend the wire which we had served with sacking and had passed through the anchor hawse.

The tidal current was just changing to run Eastward and as the stream increased the “Foresters Centenary” could make little headway, and progress became slower and slower. The “Foresters Centenary” held on, however, and although conditions were bad, we were able to keep the “Gold” more or less heading in the direction we wanted to go and at about 3.50 a.m. the Wells lifeboat “Cecil Paine” came off.

|

| Note: Chart not for Navigation |

The “Cecil Paine” gave us a rope which we made fast, passing it through the barge's starboard hawse pipe, with a somewhat longer scope than the wire fast to the “Foresters Centenary”. With both lifeboats going ahead, we made better progress and arrived off the entrance to Wells harbour at about 6.30 a.m.

|

| Wells Lifeboat "Cecil Paine" at Gorleston |

I was steering the “Gold” and I turned her to follow the lifeboats in across the harbour bar, but just as we were about to enter, the “Gold” took several heavy seas aboard her, and sheered violently to port. I was unable to hold her and she parted from both lifeboats.

The wind was now blowing from the SE by S, and the ebb tide was running out of Wells Harbour, as it was now passed high water. The result was that the “Gold” drove out to sea, heading all ways and I could not control her. Considerable water was coming aboard and it was impossible to get from the wheelhouse forward with risk of being swept overboard.

The “Gold “ drove” out a considerable distance before the lifeboats could get to her and make fast again.

|

| Note: Chart not for Navigation |

We hove in the parted wire and rope and again made the “Cecil Paine” fast with her 3½ inch rope from the port bow and the “Foresters Centenary” from the starboard bow.

The two lifeboats then towed the “Gold” to Holkham Bay and we anchored her there at about 8.30 a.m. in a position about 1 mile WSW of the entrance to Wells Harbour. We found better water there, and after paying out as much chain as we could on the anchor, we left her there and boarded the “Foresters Centenary” and proceeded to Wells Harbour. With the 3 other member of my crew, I had been on board the “Gold” for some 7 hours in exceedingly uncomfortable conditions.

|

| Note: Chart not for Navigation |

At about 2.45 pm the “Cecil Paine” and the “Foresters Centenary” proceeded out of Wells Harbour with the crew of the “Gold” on the “Foresters Centenary” and we proceeded to where the “Gold” had been left and found her riding safely at anchor where we had put her.

I went aboard the “Gold” with 3 of my crew , the crew of the “Gold”, and John Christopher Cox, one of the Wells lifeboatmen , who had local knowledge of the Harbour which was a very awkward one to navigate.

On getting on board, we made the lifeboats fast and hove up the barge's anchor and got under way. The crew of the “Gold” went into the engine room and tried to get the engine going, leaving the navigation of the vessel to the lifeboatmen. On getting round the corner of Holkham Bay we experienced rough conditions, with a heavy ground swell and when approaching the Harbour the barge rolled and took water over her deck. When we got off the entrance to the Harbour the Wells lifeboatman, John Christopher Cox, took the wheel of the “Gold” and we entered the Harbour.

The “Gold” had a big bluff bow and she was difficult to steer and when we had proceeded up the Harbour channel as far as the lifeboat house, Mr. Cox went on to the barge’s hatch and acted as pilot, whilst I and one of my crew, Mr. Scotter, took the wheel and steered under his direction. We had considerable difficulty in getting the “Gold” up the winding Harbour channel and when we came about half-way along and were negotiating a horse-shoe bend, she took charge and swung completely round. We then had to cast off the lifeboats from forward and make them fast aft, and they towed the “Gold” stern first for about half a mile until she was through the horse-shoe bend, when they again made fast forward after swinging her, and towage was continued until the “Gold” was safely moored at Wells Quay at about 6 pm.

|

| Note: Chart not for Navigation |

End of Statement of Robert Henry West

2nd Coxswain of the "Foresters Centenary"

|

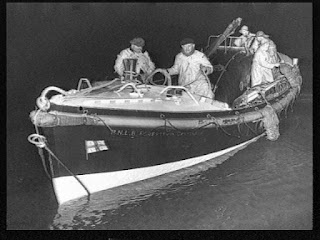

| "Foresters Centenary" returning at night |

The salvage claim was disputed by the owners of the barge and so the legal proceedings led to a trial date at Admiralty, Probate and Divorce Division of the High Court in London. Henry “Downtide” West and I travelled to London and met our barrister Mr. Hayward QC the day before. In the evening, I had arranged to meet a cousin of my wife who was a manager at the Grosvenor Hotel.

The following morning “Downtide” and I went to the High Court to be prepared to enter the witness box in the case called before Mr. Justice Wilmer. As proceedings started, the barge owner’s barrister asked for a short adjournment so that a settlement could be attempted. The legal parties all left the court room.

Sometime later the learned gentlemen returned and we all stood for the entrance of the Judge. Our barrister, Mr. Hayward, informed the Court that agreement had been reached to the effect of a settlement of £600 [£15,000 at 2016 values] plus expenses.

The Judge said that he was happy that a settlement had been reached but disappointed not to hear about the salvage operation which was considerably more interesting than the usual divorce proceedings that came before him each day.

The barge “Gold” was in trouble again on 12th February 1973, nearer her home port, when the Sheerness lifeboat had to stand by her. The final fate of the "Gold" has not been found, but the “Silver”, the last of the three barges, was operational until1984.