Before pleasure craft were widespread, most of the service calls to the Sheringham lifeboat were either for the local fishing fleet or to the merchant shipping that passed a few miles north of the town. There were typical examples of both types of call in 1949.

The year did not start well, as in the first few months a low water launch to local fishing boats had to be aborted, due to lack of manpower and no launching tractor of any description available at Sheringham. Fortunately, there were no serious results and all the boats landed safely. After the war, manpower problems affected many towns like Sheringham as there had been a steady decline in numbers over the years, compared to pre-war days when there were plenty of fisherman to launch the lifeboat.

| |

| Launching the lifeboat in the 1930's |

During the war the Sheringham lifeboat's Honorary Secretary arranged with the commander of the local army garrison to have available 40 solders day or night to launch the lifeboat. This arrangement worked well despite the soldiers not being experienced in boat handling or properly equipped.

|

| A Wartime Launch |

After the War, with fewer fishermen available to launch as well as crew the lifeboat, launching was a real problem when most of them were out fishing.

|

| The Clayton Tractor |

We received a rather antiquated Clayton tractor a few weeks after the failed launch.

This could not go too far into the sea but it meant that there was never another failed launch at Sheringham.

The lifeboat service to local fishing vessels took place on 22nd April 1949. I was going in my uncle's crab boat ‘Acadia’ when a sudden NW breeze sprang up. We managed to get back to the beach through the swell, along with a few other boats. Several crab boats were still off, so those that had got ashore ran to the lifeboat house where the ‘Foresters Centenary’ was already being prepared for launching. The sea was off the bottom of the slipway making it difficult to launch as there was no room to attach the tractor. Coxswain ‘Sparrow’ Hardingham did a good job in getting the lifeboat afloat safely under those conditions.

The crab boats and crews who were still at sea were:

‘Liberty’ crewed by Billy ‘Cutty’ Craske (Snr.) and his two sons Billy ‘Cutty’ (Jnr.) and Teddy ‘Lux’ Craske

‘June Rose’ (Eric Wink)

'Boy Billy' (2nd up)

(Jimmy 'Mace' Johnson)

'Her Majesty'

(David 'Demon' Cooper)

My cousin Richard Little and his uncle Stanley Little had a narrow escape in ‘Joan Elizabeth’ (YH435), as they came in. The surf came on board and stopped the engine at a critical moment nearly capsizing the boat. They managed to row ashore.

‘Liberty’ and ‘June Rose’ were the last to get back to the beach. The engine on ‘June Rose’ had cut out and she was being towed by ‘Liberty’. ‘Foresters Centenary' took over the tow and we brought her close to the shore so that she could be rowed in. Eric Wink thought that water had got into the engine’s carburettor, due to the sudden squally weather.

A few weeks later on the Tuesday 3rd May, the Sheringham lifeboat launched to a completely different type of casualty. The ten thousand ton Panamanian tanker ‘Barren Hill’, with a cargo of petrol, went aground on the Sheringham Shoal, 5 miles out.

|

| 'Smoky Hill', sister ship of 'Barren Hill' |

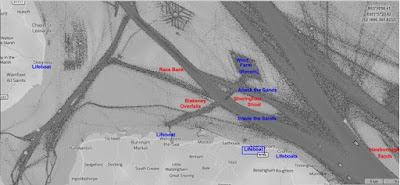

This was one of several large merchant ships that got into difficulties after the war and the reason is clear in a recent traffic density map . Much East Coast shipping used the inner coastal route "inside the sands":

Before more accurate navigation instruments and radar were installed on every merchant ship, a mis-calculation of course, tidal stream or wind direction could result in grounding on Sheringham Shoal, or on the beach in foggy weather.

There was a fresh NE breeze when we launched to the 'Barren Hill' at 3.25pm, and also the tide again was at the bottom of the slipway, which caused difficulties for coxswain ‘Sparrow’ Hardingham.

|

| 'Foresters Centenary' Launching to Tanker 'Barren Hill' |

The lifeboat’s whip aerial was lost when we were hit by a big sea on the starboard quarter while going out. A piece of wire was attached to the aerial base on the aft end box and we could keep contact via a relay with the Dudgeon Lightvessel.

We arrived to find the ‘Barren Hill’ well aground in south side of the Shoal and as is the custom the Second Coxswain, Henry ‘Downtide’ West (no direct relation) went on board her. The captain said to ‘Downtide’ that he had radioed for tugs and that the crew of 43 were in no immediate danger. ‘Downtide’ obtained a length of brass rod from the ship’s engineer to make a temporary repair to the radio aerial. So we then stood by for many hours until two tugs arrived. Overnight, attempts were made to refloat the tanker but these were unsuccessful.

After 11 hours at sea in poor conditions we returned to the boathouse to change into dry cloths and refuel the lifeboat. We were returned to the ‘Barren Hill’ by 9 am on the Wednesday and stayed until 2pm when we returned to pick up a Salvage Officer who was transferred to the ‘Barren Hill’.

Two more tugs arrived from the Humber but again the sands held her fast.

Meanwhile the tanker’s captain had arranged for a fuel barge to lighten the ship’s load and this arrived late on the Wednesday evening. Five more tugs arrived, making a total of nine and at the third attempt at high water on Wednesday night the tanker was refloated.

The captain said all was well and we returned home.

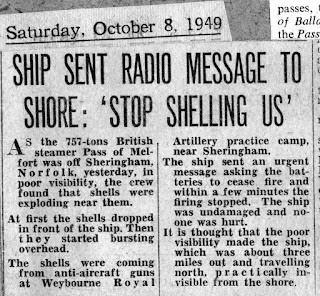

Ships coming too close inshore could experience problems as well. Henry kept the following press cutting from 1949. The Royal Artillery training centre ‘Weybourne Camp’ is now the Muckleburgh Miltary Museum.

Henry did not keep a log of all the lifeboat services that he took part in as a crew member from 1946. However by the end of 1949 the lifeboat’s bowman, Jimmy Scotter, reached retirement age and an election amongst the lifeboatmen was held to select his replacement. Henry put his name forward.

In December 1949, Henry was elected bowman of the Sheringham lifeboat – he had just turned 26 years of age.