At the beginning of 1950 I was appointed bowman of the Sheringham Lifeboat. Commands made by the coxswain and second coxswain, stationed in the stern of the boat, were carried out forward by the bowman himself or under his instruction.

The bowman was kept busy in a single screw Liverpool type lifeboat, such as ‘Foresters Centenary’, as he had to organise the stepping of the foremast and setting the mainsail if required. Anchor drill and securing alongside a vessel in distress or a quay when landing survivors were also a part of his duties. Further, at Sheringham, the lifeboat permanently carried a bow strop, so that when returning to the beach she could be pulled quickly up the shingle bank and away from the surf.

The boat's samson post was essential for the bowman’s work.

|

| A later bowman, Arthur Scotter, working on the Samson post |

A month later a brand new launching tractor, T55, arrived to replace the old Clayton model. It was a Case LA, built by Roadless.

|

| Case LA, T55 after transfer to Newbiggin in 1958 |

This was more powerful than its predecessor and could supposedly operate in 8 feet of water but the drivers did not need to go that far out as ‘Foresters Centenary’ drew less than 3 feet of water. There was a powered capstan behind the driver’s seat. T55 served Sheringham well for many years and there was space for it in the boathouse.

|

| Tractor T55 parked behind the lifeboat |

|

| Twin Screw Liverpool Class |

|

| Single Screw Liverpool Class |

Also, there was a growing worry about the single AE6 petrol engine in ‘Foresters Centenary’ failing at a critical moment during launching.

An opportunity arose in August 1950 to air these issues when the Chairman of the RNLI visited, as part of his tour of the coast. Coxswain Hardingham made the crew’s feelings known, as reported in the Eastern Daily Press on 1st September.

|

| From the Eastern Daily Press 01/09/1950 |

In the end, a twin screw Liverpool class lifeboat was never stationed at Sheringham. Henry never said why this did not take place. One explanation could be that a series of lifeboat disasters occurred at Bridlington, Fraserburgh, Arbroath and Scarborough in the early 1950’s which may have resulted in re-allocation of the twin screw lifeboat to another station.

A few weeks after Earl Howe’s visit, the ‘Foresters Centenary’ was called on an extensive rescue mission which must have tested boat and crew. Several decades after the event, Henry wrote the following account of the ‘Gaia’ rescue in a birthday card to his wife Betty, as the dates coincided.

At 8.50am on 11 September 1950, Dudgeon lightvessel radioed that a sailing yacht was circling the lightvessel and required assistance.

The ‘Foresters Centenary’ was launched at 9.05am into a rough sea with a strong SW breeze blowing. Some crew members, including myself from ‘Our Boys’, were transferred to the lifeboat from their fishing boats. The ‘Foresters Centenary’ then proceeded to the position given. Nearly all the others in the crew were still those that had served in her in the War.

|

| 'Foresters Centenary' under sail |

Coxswain Hardingham ordered up the mast and sail, for the ‘Gaia’ was 26 miles NNE of our station and he wanted to conserve fuel for such a distance from land.

After over 3 hours, the yacht ‘Gaia’ was sighted by the lifeboat near the Dudgeon Shoal. The weather was squally with a force 6-7 SW wind in that area.

We went alongside the casualty which had 4 persons on board. The ‘Gaia’ was on passage from the Tyne to Chichester via Harwich and her mainsail had blown away along with one of the jibs.

A towing warp was made fast and the long tow back was started, against wind and tide. We arrived back at Sheringham at 6pm – nine hours after launching.

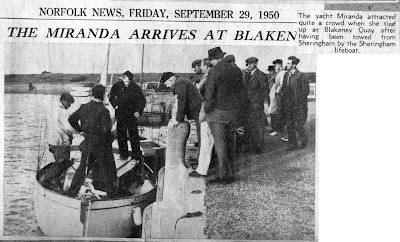

'Gaia' and 'Foresters Centenary'

The lifeboat was refuelled at sea, from a crab boat, as the station's Honorary Secretary had given permission for the yacht to be towed to Great Yarmouth. After the lifeboat was refuelled we proceeded to Great Yarmouth, arriving at about 11pm. There was a quick tie up at the Town Hall quay and we left the harbour around 11.30pm and arrived back at 4.40am, after a rough trip home along the coast. Overall, a 19 ½ hour service.

|

| 'Gaia' Rescue - 19.5 hours at sea |

After securing a bow-line from the lifeboat’s Samson post to the bollard on the quay at Blakeney at the end of the rescue, I forgot to release it from the Samson post when we left Blakeney harbour.

The result was that the line attached to the lifeboat’s bow strop was buried under the bow-line when we returned to station. This made a delay in releasing the bow strop for the shore crew to attach to the winch wire.

I will always remember what coxswain Hardingham said to me afterwards about this error on my part : “You let me down”.

|

| Coxswain John Hardingham, during the War |

John ‘Sparrow’ Hardingham had been a lifeboatman for over 42 years and his time as coxswain had been extended one year over normal retirement age.

He was said to very rarely smile. He was in the whelker ‘Welcome Home’ when she was sunk in February 1931 and his partner Jack Craske never recovered consciousness despite the efforts of the Cromer lifeboat crew.

Elections for both coxswain and second coxswain posts were to be held before the end of the year. After being in the bowman’s post for less than 12 months (there had been few lifeboat calls up until September) and following John Hardingham’s remark, I didn’t consider applying for the second coxswain’s position.

However, it was on a Sunday afternoon stroll with Betty and our young son, that we met Teddy ‘Lux’ Craske, the First Mechanic of the lifeboat.

The Craskes were one of the most respected fishing families in Sheringham and it was Teddy’s brother Jack who was lost in the ‘Welcome Home’ tragedy. As with ‘Sparrow’ Hardingham, Teddy had decades of lifeboat experience and so everyone took his advice seriously, when he gave it.

Teddy came to the point “Why don’t you apply for the Second Coxswain’s post Henry?” I didn’t need to explain about ‘Sparrow’ Hardingham’s recent comment as he knew full well what went on. To be honest, Teddy’s suggestion wasn’t expected and surprised both Betty and well as myself. All I could say at the time was that I would think about it.

|

| Eastern Daily Press 18/12/1950 |

Elections took place in December 1950 and I put my name forward for the Second Coxswain’s post. Fellow crewmen, most of whom had many decades more experience of lifeboat work, voted me into the Second Coxswain’s post. I was 27.

John Hardingham’s time in the lifeboats ended with a service to assist a lost Dutch steamer, ‘Johanna de Velde’.

|

| From the Lifeboat Journal |

|

| From the Eastern Daily Press |

What the press cutting doesn’t mention is that ‘Downtide’ West, the then second coxswain, went on board the steamer to point out their position on the chart. He returned to the lifeboat with what he thought in the darkness, to be a bowl of goldfish. It turned out to be orange pieces floating in gin.