|

| My Father-in-Law |

Gardening was his main outdoor activity and he worked two allotments in Sheringham.

However, he had one final surprise to spring on us all in his later years.

Only rarely did he talk about his experience in the trenches of the First World War but his wife Dorothy told me that he was gassed and had shrapnel in his hands.

You could say that I was adopted by Jack Avery and his family. Betty and I, with our children lived next door but one from Jack and the rest of his family. We were a little community away from other fishing families. When disputes broke out amongst the fishermen I was able to avoid getting involved. People would say “ Henry, you’re best well out of what’s going on”.

Jack Avery and I used to go out on a summer evening in his pre-war black Austin to one or other country pub for a quiet pint. Quite often I would be listening to what he had to say when he would suddenly stop and exclaim in his Derbyshire accent “Sup up Henry you drinks like a lady!”

As Jack had a major influence on Henry, a short biography seems appropriate at this stage:

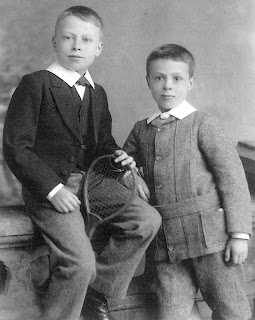

Jack Avery was born in Derby in 1884. Before this, his parents had moved from Norfolk when his father had left Taverham paper mill near Norwich to work at the Midland Railway centre in Derby. His father was also an Elder in the Methodist Church.

|

| Jack & Ernest Avery (c.1894) |

He moved to Cromer and the next photo of him is in what appears to be the chorus of a choral or operatic society in around 1910.

|

| A Cromer music society about 1910: Jack 3rd left on back row |

It was during those years at Cromer that Jack met Dorothy Roper who was an assistant at the family’s dairy shop in Church Street, Cromer. They married in the parish church in 1913.

|

| Dorothy Roper c1910' |

|

| Church St., Cromer in 1900’s |

Jack returned to teach in Derby as pay rates were better than those in Norfolk. He also joined the local Territorial Army; the 1st Contingent of the 5th Battalion of the Notts and Derby Regiment, known at the 1/5 Sherwood Foresters, in around 1913. The Territorials were mobilised when World War I was declared in August 1914 and Jack left home for training camp and eventual transfer to the Western Front in February 1915. A bundle of Jack’s original World War I documents and photographs was discovered in 2014 and is now with the Mercian Regiment archivists at Nottingham Castle.

|

| Jack (left) in Autumn 1914 |

“Major General Stuart-Wortley was commander the North Midland Division, of which the Sherwood Foresters were a part. They had suffered nothing but ill luck since crossing to France in 1915. Firstly the Division had held a dangerous part of the Ypres salient, then in October, as part of the Battle of Loos, it had been thrown in broad daylight against the notorious Hohenzollern Redoubt and had lost 3700 men in ten minutes."

|

| Jack (left) at Vimy Ridge, Jan. 1916: Photo by French officer |

"Finally the North Midlands Division had come to the Somme, not to take part in the main attack but in a diversion at Gommecourt, of doubtful value.

On the morning of the 1st July 1916, the six battalions of the North Midlands Division attacked the north side of the Gommecourt salient but all were repulsed, with five of the six battalion commanding officers being killed or wounded. The German army was strongest in the north of the battle zone; opposite the North Midland Division. Captain J. L. Green (RAMC) a medic attached to 1/5 Sherwood Foresters was awarded a posthumous VC’s, one of only nine awarded on the worst day in the British Army’s history."

|

| Sherwood Foresters on First Day of Somme |

The North Midland Division lost a total of 2455 men on that day. The losses would have greater but Major General Stuart-Wortley did not follow orders for another full attack in the afternoon of 1st July. Many hundreds of men’s lives were saved by his decision but he lost his commission and was sent back to Britain.

The Sherwood Foresters remained on the Somme for a year and were able to collect the remains of those fallen in No Mans Land since 1st July when the Germans suddenly retreated in February 1917."

Jack was promoted to Company Sergeant Major and transferred to the Graduate Officer Training course at Worcester College Oxford before returning the Western Front. He was re-assigned to the Royal Welch Fusiliers, as a Second Lieutenant.

|

| 2nd Lt. Jack Avery (circled) in Royal Welch Fusiliers, 1918 |

Jack’s final surprise is best described in the following extracts from a press article.

“He Left Inkpots for the Lobster Pots:

When Jack retired from teaching there were the usual good wishes for a happy and peaceful retirement and visions of his pottering by the fireside. But for the ageing school master with a secret ambition, life was about to start. At the first opportunity the family moved to Sheringham – and Jack turned sea fisherman.

Now going on his 70th year, he’s as seasoned an old salt as ever beamed from a seaside postcard. Go down to Sheringham’s East Slipway any day and there you’ll see Jack, every bit the part in his blue fisherman’s jersey and seaboot. Sorting out his catch of crabs, lobsters and mackerel or hauling in his boat over the shingle after his latest visit to the ‘pots’.

The old schoolmaster is as much a source of amazement to his fisherman colleagues as he is to old boys from his former school and friends from Derby.

|

| Jack Avery (l) with Jimmy 'Paris' West and other Sheringham Fishermen |

|

| Jack Avery (left) with Jimmy ‘Paris’ West |

|

| L-R: Henry, Jimmy ‘Paris’ West, Jack Avery and Jack West |

|

| ‘Miss Britain’ in 1955 with Jack Avery’s Grandson on board (right) |

Sadly, World War I may have caught up with Jack Avery by the late 1950’s. Jack’s health deteriorated and he died in 1959.